LYON on TEDx & Latest project SOMOS BRASIL (22/11/2016)

Who are we? Lyon asks us to question how our identities are formed. Using Somos Brasil (We are Brazil), a multi media photography, sound and DNA project, he brings us images, stories and ancestral DNA to examine modern Brazilian identity. In turn he asks us to consider what drives us and what we can become.

LYON’s interview about WE:deutschland (15/11/2018)

SOMOS BRASIL feature on Atlas on the future (10/11/18)

LYON’s Four Elements in Sotherby’s Made in Britain (20/03/2018)

‘Marcus Lyon in one of the leading contemporary British photographers’ – Robin Cawdron-Stewart, Head of Sale, Modern & Post war British Art, Sotheby’s.

In the Press

British Journal of Photography, 2019

PHOTO MONITOR by Katy Barron

Katy Barron: Can we start with a summary of your career until 10 years ago, as your path into fine art photography was an unusual one in many ways? What did you do after your degree in politics?

Marcus Lyon: After leaving university I worked in a photographic studio in London sweeping floors and making the tea. I saved and bought a large format camera, travelled to America to make a 22, 000 mile road trip while building a first portfolio. One of the images made on that journey won the Benson & Hedges Gold award. That changed everything and significant international commercial work and commissions followed.

KB: How did your personal work fit into your practise?

ML: The model right from the beginning was to do nine months’ worth of commissioned work and three months’ worth of social issue-led reportage. I wanted to be involved with organisations that create significant change, so I worked extensively with NGOs focused on issues surrounding street children. The work was exhibited across Latin America, and in the process I built an understanding of the issues surrounding these children’s lives. In turn I was invited to serve on various charities boards and that drew me out of the ghetto and into leadership roles. It is a relatively unusual being an artist with governance skills but a hugely rewarding one. These events helped me develop the skillsets that led to my present role as a Somerset House trustee.

KB: At what point did your work move away from black and white and become about mass behaviours and what led you to decide to make very complicated digitally produced images?

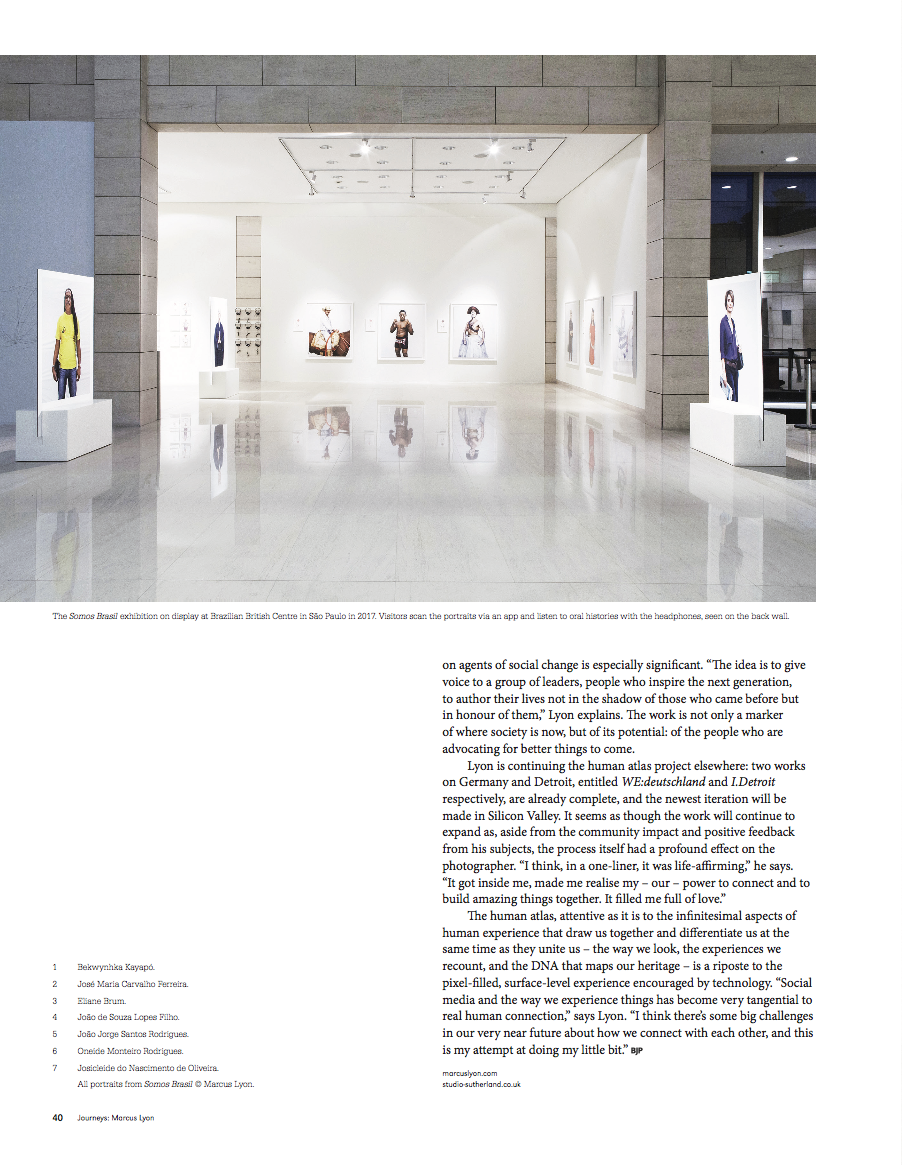

ML: I had started using digital cameras in tandem with film about five years before I produced my first large-scale constructed montage work in around 2007. I was spending more time thinking about what we are up to globally. My thoughts were all about the urban space and its role as the most significant change space of our time. I wanted to use the new processes to explore these ideas. All around me were people completely unaware of the realities of Mumbai, Chongqing or São Paulo. Indeed few had even heard of Chongqing, a city in western China of 30 million people.

KB: Please can you explain the ideas behind the BRICs and Exodus series?

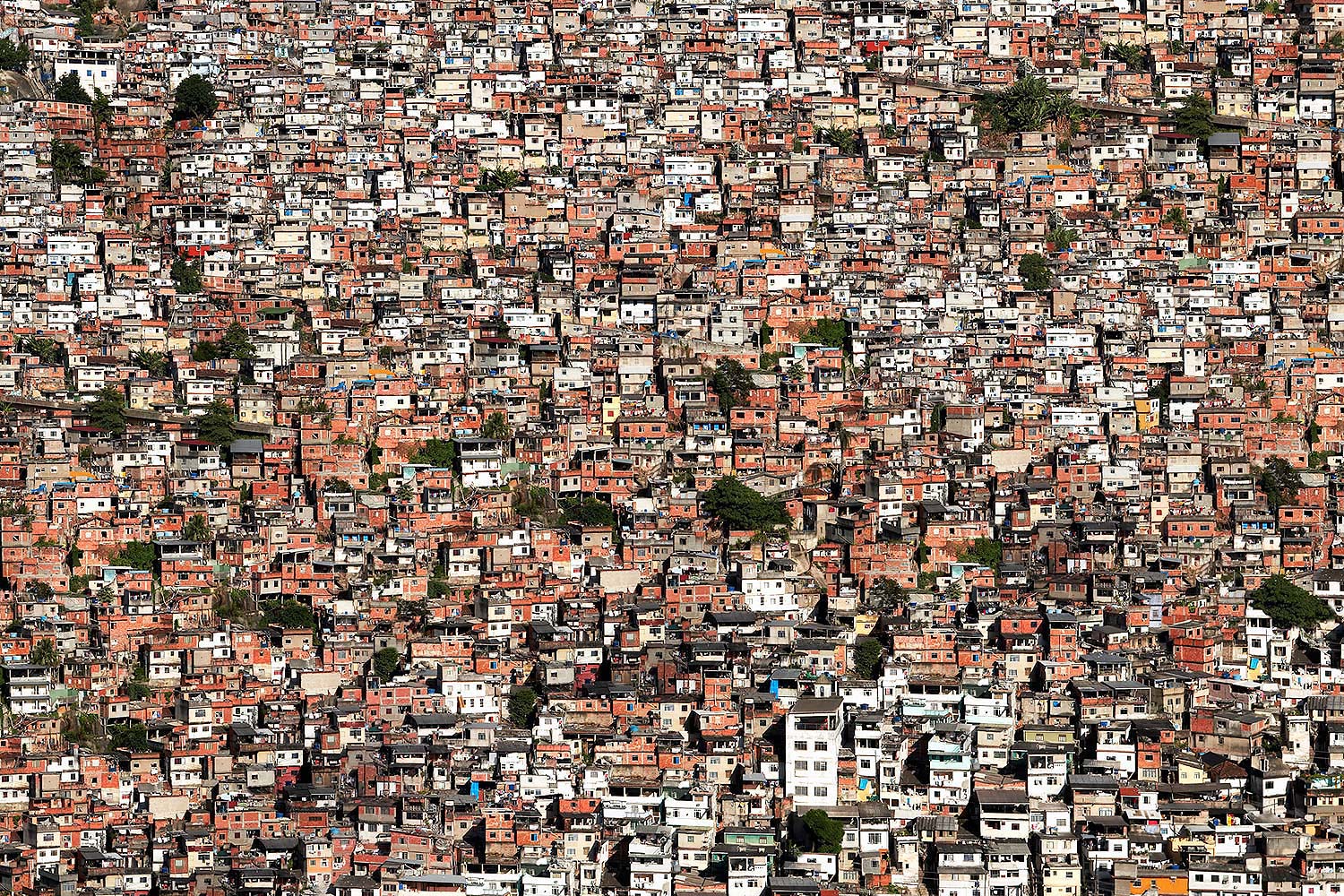

ML: BRICs is about rural-urban migration which led me to ask the question, ‘What are the other significant migrations of our time?’ So the opening shot in Exodus of Damascus looks at the unstoppable expansion of digital information that has empowered citizens, and in turn challenges the state’s ability to control opinions, actions and environments. This was the moment when I began to bring new layers to the work. For instance in Exodus II there are 750 motor vehicles to represent the 750,000 miles that I will drive as a car-owning human.

KB: What is your process and to what extent do you pre-visualise your images in advance?

ML: The images are almost completely pre visualised – I sketch them first. I try to know exactly what I want before I shoot, so there is plenty of research and thinking done in advance of any actual photography. This allows me to search for all the elements needed to build a final image. I bring upwards of 1,000 images together to create a final work that is hopefully more real that a single image. They often take up to three months to finish.

KB: The Exodus series explores mass human migration, which led you to make the new Timeout series that explores mass behaviours within the sphere of leisure. The subject matter of your large digital prints seems to have followed a clear trajectory from survival to leisure?

ML: I suppose the big question is, what do we do once we’ve found safety, shelter and sustenance. So it’s all about looking at the behaviour of the billion who no longer have to chop wood and carry water.

KB: How far is this critical, is there an environmental message?

ML: I have my own opinions, but I don’t think they’re in the work. The work endeavours to be an accurate representation of our behaviours, and I think it’s up to people to look at it and then be amazed or shocked.

KB: As an artist who wants to sell this work, do you feel under pressure to de-politicise it?

ML: No, because collectors are an eclectic and sophisticated bunch and the work appears to appeal to a wide audience despite how some might see it. I think what’s interesting in a subversive way is that one of my images ends up in a corporate boardroom or private collection where people will have to ask ‘is that what we’re doing, is this who we are?’

KB: Can you explain why you always put yourself in every photograph? Is that ego or an admission of responsibility?

ML: Well, probably. I’ve never been asked that question from that angle, but there are lots of reasons, and hopefully it works on several levels. I spend a lot of time around children and if you show them one of my images, they engage for a few minutes. However, if you tell them there is little Marcus and ask them to find the artist, they stay glued to the work. And yes there is definitely an admission of responsibility in the process. I’ve flown half way around the world for these pictures. So if I can’t be in them and visualise my responsibility, my complicity, then it would be wrong.

KB: They are the sum of reality, aren’t they?

ML: Yes, they’re a sum of many things. Photography is very liberal with truth, because you can crop a photograph, and really not show the truth at all. The Exodus III image of contra trails over London is interesting, because people look and ask, ‘Two hours, are there that many?” In reality there were far more.

KB: What advice would you give to young photographers who are starting out? You have negotiated your way through the art world with both critical and commercial sucess.

ML: I think the most important thing is to find your own voice. I think that comes slowly, and I’d say I’ve only really found mine properly in the last ten years. Day to day I think the three keys are hard work, great ideas and constant reinvention.

‘The Bigger Picture’

Introduction and interview by Alasdair Foster

This series of articles looks at the work of photo-artists who have a different ‘way of seeing’ – one that seeks to move away from the conventions of photography as document. How would you describe your ‘way of seeing’?

I have always been focused on the primacy of the idea. It is the key to unlocking meaning and one’s guide through the act of making. I combine this with a strong commitment to the creative process of pre-visualisation – to having a clear mental picture of the finished image in my mind before I even pick up a camera, choose a location or decide on a subject. This has helped focus my work into clearly defined projects, each with its own concept and rationale built into it.

In your series ‘BRICS’ [an acronym for five major emerging national economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa], you focus on the mass urbanisation that was already sweeping the world by the end of the first decade of this century. How did this series come about?

I had been undertaking pro-bono photographic work for non-government organisations with a social mission. A decade on, I became the chairman of two international development agencies working with urban street children. This led to a deep personal reflection upon the urban space globally. In particular, I chose to explore the megacities of the developing world, recognising these enormous urban spaces as places that illustrate both the opportunities and the challenges we face in a world where over half the global population live in cities.

You are notable for the amount of time you dedicate to volunteering for charitable and non-governmental organisations. Do you feel your life as an artist is separate from, or intimately bound up in, your public service work?

My work in Civil Society roles is integral to my life as an artist. Without service to community what are we as individuals in a human society? The role of the artist is to communicate deep truths and seek new ways of thinking. What better way of doing this than through service to one’s fellow men and women?

‘BRICS’ took a broad view of a real scene, in the following series, ‘Exodus’ and ‘Timeout’, you extended the visual possibilities across time and space, creating something that goes beyond the traditional understanding of the photograph as the document of a single moment.

I wanted to find a visual language to express deeper truths about our global mass behaviours to honour the extraordinary influence humankind has on the planet. The finished picture is constructed from hundreds, sometimes more than a thousand, images. I did this to challenge the ‘tyranny’ of 1/125th of a second.

‘Exodus’ is an exploration of the significant migrations of the early 21st Century, as people, goods and services circumnavigate the planet in increasing volumes and at accelerating speeds. I want these images to provoke questions about the huge changes in contemporary society and to do this through large-scale representations of the key themes that influence globalisation in the modern world.

‘Exodus VI’ is a good example…

Making that piece was a particular joy for me, because I shot it during my honeymoon. But it was also a challenge as it involved working high above the sea in a helicopter with the doors removed. The final picture is built from approximately 500 images combined to create a harbour view that resonates with what it actually feels like to witness the West Lamma Channel. It is one of my personal favourites.

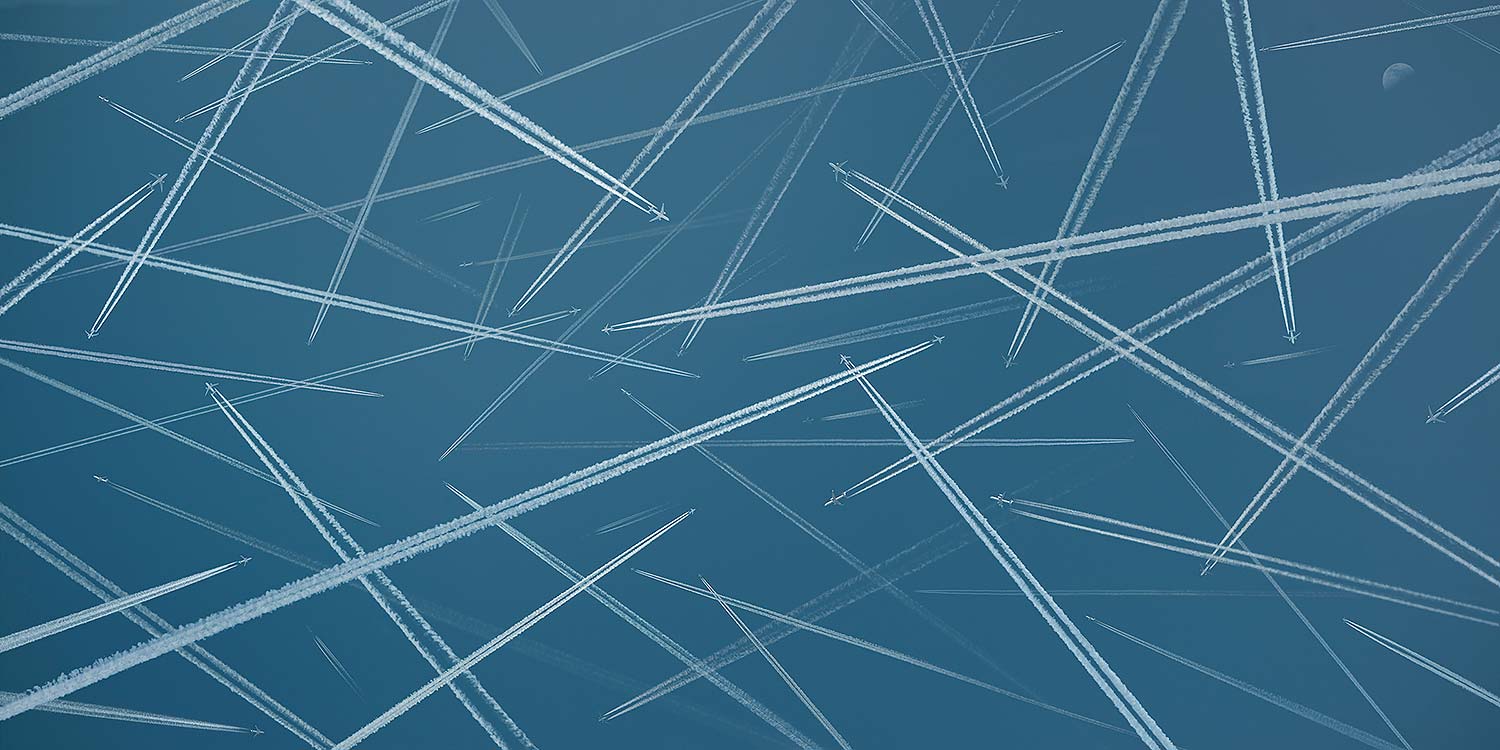

In contrast, ‘Timeout’ focuses on leisure…

There are a billion people on the planet that no longer need to struggle to meet their basic needs. In their search for meaning they turn to another basic human instinct: exploration. Whether we travel by budget airline or luxury yacht, the human race defines its modern existence through its search for ‘redemption’ from work through recreation.

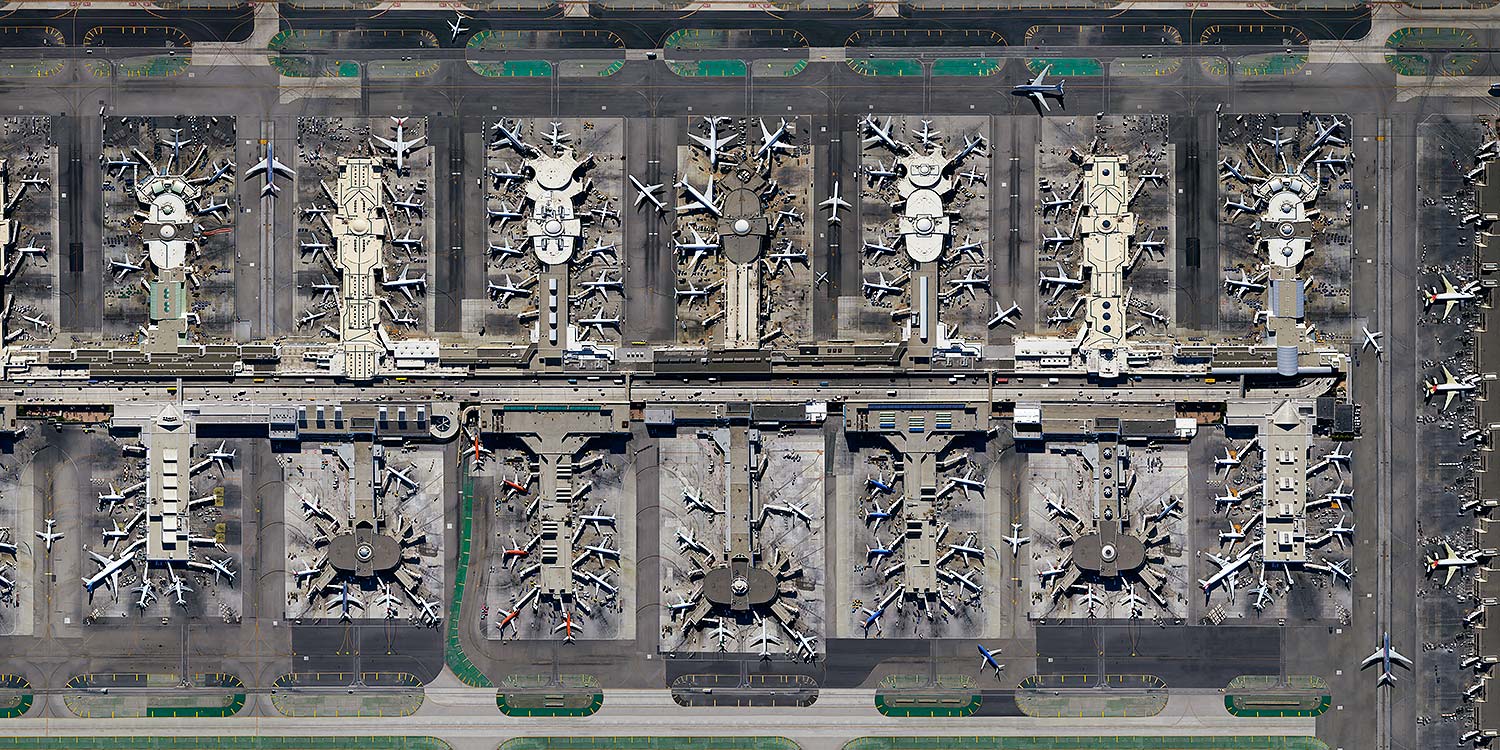

But it is an equivocal ‘redemption’; for example, in ‘Timeout II’. This was shot at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and based on an initial sketch I made in which an imaginary airport is constructed like the spine and ribs of a skeleton. Having researched the layout of many airports, LAX proved to be the best suited to this creative vision. The final picture is a composite of more than one thousand separate images. It honours these extraordinary structures, which play such a central role in our globalised world, while also raising significant questions about humankind’s ecological footprint in the age of the Anthropocene.

In 2012, you photographed the Paralympic Games in London for a series called ‘Stadia’. While many who photograph the Paralympics feature the individuals involved, your images take in the entirety of the scene. Why did you choose this approach?

The images endeavour to inspire the viewers with a deeper sense of the complete human story behind the games, illuminating the architecture, sport, media, competitors and crowd as equal partners in a spectacle of biblical proportions. In the twenty-first century, super-large-scale sporting events have become a form of mass human worship. The stadium has become a modern temple, defining our Media Age. Backed by enormous corporate funding, the sports stadium has the ability to transform and renew. In many ways they are a modern expression of the traditional religious concept of redemption: incarnation, struggle, glorification and, ultimately, the salvation of victory.

It is always a challenge for artists to make a living from their work. How do you balance your creative and financial needs as a photographic artist?

Many artists support their art-making through earnings from other sources such as teaching. I have been fortunate. I established my studio in the early 1990s when London was a very affordable place to live and work. I established my own gallery, The Glassworks, and sell most of my work directly to clients or at international auction. By selling directly to corporate and private collectors I not only avoid art-dealer commission fees but also develop the kind of long-term relationships that help maintain income stability. As a result, I have never had to seek a ‘day job’ to support my artistic output.

That first group of photographic projects engaged our sense of scale and time in a number of different ways. And, although people did not feature directly in many of the images, they all address issues that are driven by us human beings and by the historical moment in which we find ourselves. The next group of projects have the collective title of the ‘Human Atlas’. In them, you address those earlier ideas through a different approach; one that places people centre stage and explores not simply who they are but their individual lineage. The first of these was ‘Somos Brasil’. It’s a multifaceted artwork, so could you begin by describing its constituent parts.

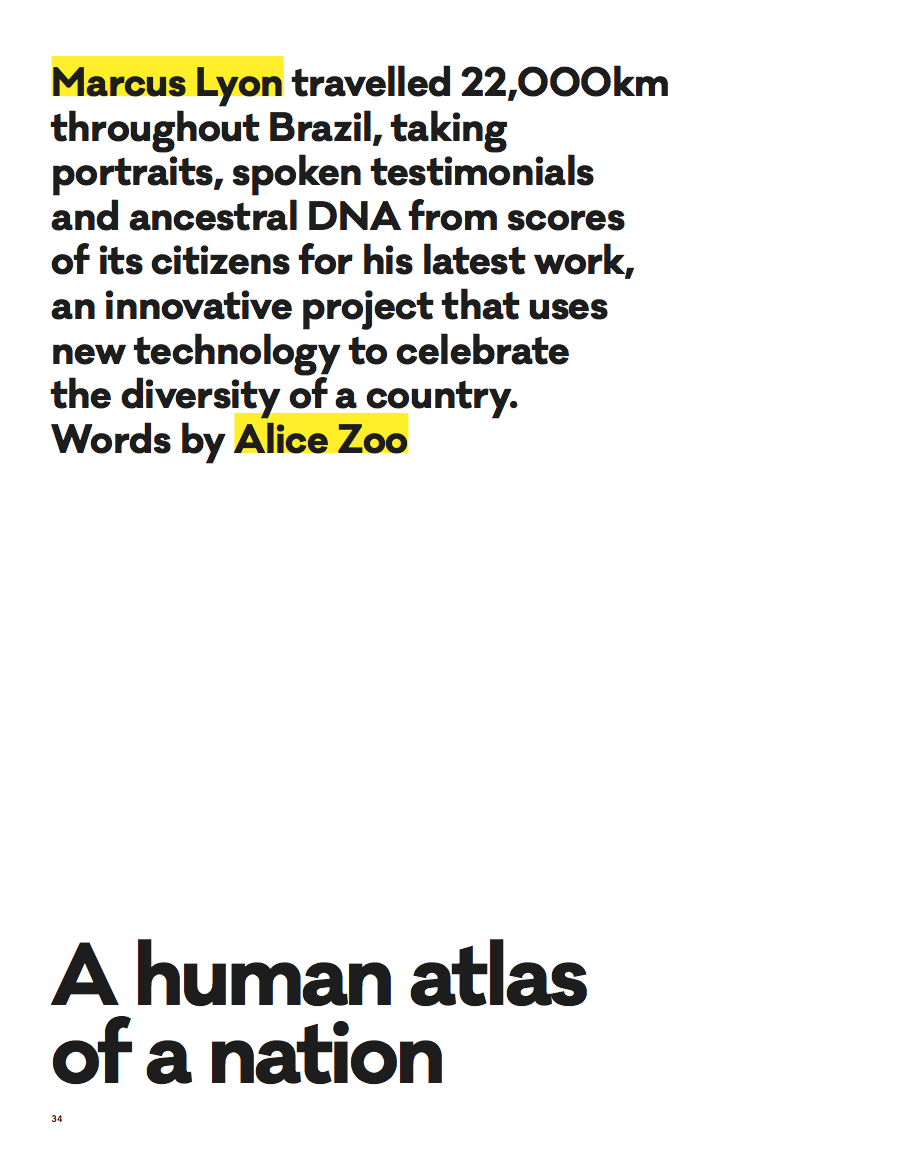

‘Somos Brasil’ explores the diversity of Brazilian identity through three interconnected approaches: photographic portraiture, oral histories and DNA mapping. Here, the insights of a photographic portrait are amplified through the voice of each individual (accessed via an image-activated cell-phone app) and infographics showing the location and relative proportion of their ancestral origins as expressed in their genes. Together these three elements mapped the ancestral DNA, personal stories and visual identity of over one hundred remarkable Brazilians.

How did you select the people to be photographed?

I didn’t. They were all nominated. We ran a six-month research process asking journalists, community leaders and local experts to propose extraordinary individuals who are creating significant change for the good in their community. Together they showcase the personal, social and cultural diversity of a nation through a group of individuals who have shown their commitment to social impact in all its forms. In turn, I hope that this will encourage each of us to reflect on our own individual identities and roles in society.

Why did you select Brazil?

Brazil sits at the epicentre of many of the most challenging issues of our time: demanding educational, environmental, economic and societal challenges. The individuals represented in ‘Somos Brasil’ demonstrate just what we are capable of when we truly re-imagine our potential to create a better future and focus on hope. These are the faces of the future: they bring light to our troubled times.

Social impact projects such as ‘Somos Brasil’ and the wider ‘Human Atlas’ are conceived and created on a grand scale. How did you go about securing the funding for such ambitious projects?

These are large-scale projects spanning several years. In order to achieve the levels of funding necessary, one has to find funders whose core mission aligns with the fundamental aims of the work. These projects focus on societal change and social impact. They attract the kind of interesting sponsors whose values lie outside the more traditional art-funding models. This work is founded on a collaboration between science, anthropology and art which has proved appealing to foundations, companies and patrons who share my commitment to the values of engaged community and inspiri leadership at a time of significant disruption.

How do the public respond to the work?

The public reaction is ‘off the scale’. So much in modern society limits human experience to ‘sound bites and swipes’. The ‘Human Atlas’ asks the viewer to slow down, to see and hear real stories. To learn once more how to look and to listen. For me, it is always a delight to witness how deeply both young and old engage with these portraits, narratives and ancestral journeys. People seem overjoyed by the opportunity to actually listen deeply and connect with others

In 2019, you launched a second project in the ‘Human Atlas’ called ‘WE: deutschland’. This also emphasises community diversity through a combination of portraiture, interviews and genetic mapping. How did this project come about?

I was approached by a company whose Corporate Social Responsibility focus was to promote a more diverse and open world. They had seen ‘Somos Brasil’ and asked me to create a new project featuring a European nation. I could choose the nation and they would fund the whole project.

Why did you choose Germany?

To my mind, the most significant changes in modern Europe are around the migration of people fleeing crisis in Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Germany sits at the epicentre of these issues and has in many ways been exceptional, taking well over a million new refugees and migrants in the last four years. Germany’s transition from the extremes of mid-twentieth-century National Socialism to being the nation within the European Union that is most welcoming to refugees deserves deep consideration. With the support of this corporate funding, we conducted an in-depth nomination process to find fifty individuals who could stand to represent the breadth of modern Germany.

What are you working on now?

I am currently working on several projects, but the main focus is on ‘i.Detroit: a Human Atlas of an American City’, a new body of work focused the change agents of the city. The ‘I.Detroit’ project, commissioned by the Kresge Foundation and in partnership with the Charles H Wright Museum in Detroit, is a deep-dive exploration of the human capital of the ‘Motor City’. We are currently at the end of the production phase and just embarking on the complex process of bringing the DNA, sound and images together in a book and exhibition. This will be published and exhibited in Detroit in mid-2020.

You have described yourself as ‘annoyingly ebullient and cheerful’. Do you think that energetic optimism is an important personal trait in how you go about your art-making?

Being deeply positive has its advantages. It helps one work through things when life’s journey gets tough. And being cheerful often brings best in others.

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making photographs?

Making images, communicating visually, has for me been the gift that keeps on giving. It has supported me emotionally and financially. Making pictures has allowed me to travel and connect with the most fascinating people. It has brought me everything… I even photographed my wife, Bel, before we first met. It has been and continues to be the greatest privilege…

LYON in Creative Review (28/04/2017)

Marcus Lyon’s multimedia project, Somos Brasil, documents over 100 Brazilians through photography, recorded sound and DNA sampling. The result is a detailed study of the ancestry of a truly global nation – and a D&AD award-winning piece of work

D&AD Yellow Pencil Award – Book Design

Over a six-month period Marcus Lyon toured Brazil exploring the most diverse corners of the country with a producer and sound recordist. Together they mapped the ancestral DNA, personal stories and visual identity of over one hundred remarkable Brazilians. Somos Brasil draws three elements of identity: visual, spoken and genetic – to cast light on the personal, social and cultural diversity of Brazil.

Idee e Lifestyle del Sole 24 ORE (09/11/17)

Somos Brasil is a multimedia exhibition and book. The project explores the diversity of Brazilian identity at the outset of the 21st century through ultra high quality portraits, image activated app based soundscapes and DNA.

The NATIONAL, UAE – Arts & Life by Ben East (30/03/2015)

Marcus Lyon is racing up the dramatic, sweeping Nelson staircase in London’s Somerset House, the spectacular neoclassical building on the banks of the Thames that is exhibiting some of his awe inspiring images. “Look at these stairs,” he exclaims, almost breathless. “Aren’t they just … fantastic?”

They are, but it’s very much Lyon’s style to find beauty and power in everything – including a 12-lane stretch of Sheikh Zayed Road in Dubai.

In 2010, Lyon was in the UAE undertaking some pro-bono charity work. His hotel was right beside the highway, so he accessed its roof to lean over the 43-storey building, and take shots of the street scene below.

“I don’t suffer from vertigo, thankfully.” he says. “But when you’re squinting through a lens for hours taking images, you do get a bit dizzy.”

The result, three months of hard work later, was Exodus II – Dubai. It’s a stunning composition, with cars and humanity seeming like distant bricks on a monstrous yet aesthetically pleasing superhighway.

Dubai residents will immediately see one thing, however: the 12-lane highway has seamlessly metamorphosed into a road that has 36 lanes going each way. This is the motif running through all of Lyon’s work in the Exodus and Timeout series on display at Somerset House. He manipulates and adds to an overhead image, exaggerating its scope to layer added meaning – all the while maintaining a semblance of believability.

“For me, bringing together multiple images is a more accurate view of what impact we have on the world than a single one,” says Lyon. “It means I can explore a more nuanced truth about the way we behave and act and what we do en masse in the 21st century – there’s 750 cars on Exodus II, which represents the 750,000 miles I will drive as an average car owner. This is the bigger picture.”

And that’s the real success of the Exodus and Timeout series – they marry artistic prowess with ideas about migration, identity and globalization. Exodus IV – Hong Kong, for example, is a richly beautiful and sparklingly colourful image that makes a stained-glass window out of hundreds of shipping containers – a cathedral of consumerism. And while Exodus II also works as a brilliant piece of art it also comments on the use of the planet’s resources, there’s a more personal meaning, too.

“I was also trying to think about that sense of identity we get when we own a car,” he says. “So if you drive a Mercedes, for example, I feel differently about you than if you drive a Skoda. These modern products change the sense we have of ourselves. So if you look at that image, the positions of the cars mirror the stripes of light you get in a DNA pattern. Exodus II is as much about identity as it is about car use.”

What’s refreshing about Lyon’s work is that it never overwhelms with meanings and messages, but merely asks that we draw our own conclusions and start conversations about what we’ve done to the planet and where we are at in the 21st century.

GUARDIAN – My Best Shot by Karin Andreasson (19/02/2015)

I was in Dubai in 2010, doing a speech for a charity, when I discovered the amazing Sheikh Zayed Road. It has 12 lanes, tall buildings and skyscrapers on either side, and stretches right through the middle of the city. I booked a hotel next to it so that I could get up on to the roof. I was probably up there for about an hour and a half, hanging over, shooting straight down. You get a bit dizzy doing that.

The photograph started out as a little sketch in a book, though, just some lines, dots and ideas. Initially, I wanted to do something more music-based, but it morphed into a representation of my petrol-using life. It’s a composite of about 1,000 photos, and it took three months to make. I have a whole team of people who work with me to create an image like this, although I’m in charge of the idea. There are 750 vehicles in the end result, and they represent the 750,000 miles that I and the average car-owner will drive in a lifetime.

Part of the thinking behind the work is that people are too visually literate and the world too fabulously complicated for me to say what I want in a single shot. So I bring multiple images together to create a greater truth. I think an image taken at 125th of a second is kind of a lie: it’s a moment captured in time, but then it disappears. With multiple images, I can go deeper, be subversive. So when people see this mega road I’ve created, they instantly ask questions. Is that really the world we live in? Is this image real or not? Where do I fit in to all of this?

Although I cut my teeth on large-format photography, I now use digital cameras and computer manipulation. But I think it’s essential to make sure the perspective is still correct and the image works from one point of view. So, at the top of this picture, I made sure that you see slightly more of the sides of the buses than you do at the bottom, where you would be looking straight down on them.

In the modern world, photography is instantly disposable. What I think is fascinating about images made this way is that they are really gluey. You get mesmerised by them. Your eyes are drawn to the whole composition, yet they can’t quite settle anywhere. As a final touch on all my creations, I insert a little Marcus. In this one, I’m in the top left-hand corner riding a bicycle.

CV

Born: Exeter, 1965.

Studied: Political science at Leeds university

Influences:Norman Borlaug, Ray Metzker, Edward R Tufte, Gil Scott-Heron

High point: “Today.”

Low point: “None. I’m annoyingly ebullient and cheerful.”

Top tip: “Have ideas, work hard and reinvent.”

TELEGRAPH – Migrations, megacities and mankind on the move by Cam (10/02/2015)

With his large scale works – Exodus and Timeout – photographic artist Marcus Lyon explores themes of consumption and migration in an ever-shrinking world.

Lyon has travelled the world, from Los Angeles to London via Hong Kong and beyond, to create limited edition images of mass transit systems, transport hubs and huge urban conurbations – claustrophobic vistas which seem to go on and on. Strangely formal yet abstract these aerial images are at once fantasy and reality.

His technique is simply but painstaking. Lyon splices together hundreds of images from an existing scene (usually shot from above) to create an agglomeration which mirrors global themes of rampant consumption, massive urban sprawl and the huge gulf between rich and poor. If these chaotic scenes seem too large to be true it’s because they are.

“Emotionally and environmentally these mass ideas, actions, movements of people, production processes … are so huge that no single image can define their influence,” says Lyon. “So I have endeavoured to create new visual languages within which I can communicate a deeper truth.”

The work is speculative. How will the world look in 10, 20 years time? Perhaps Lyon has shown us.

PHAIDON Marcus Lyon’s photos from the future by Alex Rayner (02/02/15)

The British image maker explains how his landscapes capture our globalised world at its most extreme.

When I was born, in 1965, there were a billion people living in the urban environment,” says the British photographer Marcus Lyon. “Now there are closer to four billion, and by the time we get to 2030, there will be five billion. That’s one of the great migrations of our time.”

Lyon worked as a reportage photographer for the likes of Amnesty International in the developing world throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, shooting images in the slums and ghettos of the rapidly growing cities of Latin America, Asia and Africa.

When, in 2008, the UN estimated that, for the first time, more than half of the world’s population was now living in urban areas, Lyon felt the urge to document this change. Yet he knew that no one image could accurately represent this reality. Instead, over recent years he has been creating a series of finely manipulated photomontages that capture our urban, mechanised, out-of-kilter world.

His BRICs artworks, created 2008-10, conjure up the dizzying megacities of Brazil, Russia, India and China; his Exodus images, made 2009 – 2014, exaggerate the shipping traffic, flight paths, road systems and freight yards that serve this urban expansion; while his newest works, Timeout, currently on show in the 1st floor of the West Wing of London’s Somerset House until 1 June, considers our mass pursuits – from gargantuan golf-course complexes to endless yacht marinas – of the globe’s new leisure class.

Stylistically, the pictures might bring to mind the Düsseldorf School of photography, yet Lyon, while deeply flattered by the comparison, tries to draw from more diverse influences. His images, although manipulated, often reference genuine current-affairs, such as the tin-shack communities built on the Cape Flats outside Cape Town, sometimes described as apartheid’s dumping ground; or the West Lamma Channel in the South China Sea, one of the world’s most congested shipping lanes.

“I research the images in depth, by reading a lot of books, and articles in The Economist,” says the photographer. “To be honest, I’d say [Nobel Prize winning plant geneticist] Norman Borlaug is more of an influence than Andreas Gursky.”

Lyon, who was nominated for the Prix Pictet in 2013 and 2014, and is short-listed for the 2015 Aesthetica Art Prize, says he drafts his ideas on paper, before shooting the constituent images, often from high vantage point or chartered helicopters with the doors removed: “Then over periods of up to three months my team and I create wire frames to then meticulously build the images,” he explains.

He hopes these tweaked versions of our interconnected world will inspire dynamic conversations about our role in globalisation, yet audience reaction varies enormously. “Some people see the aesthetic and a sense of progress and opportunity,” he says, “others see a nightmare image of our future, and others don’t question it at all and see a reality.” And, perhaps, in a few years’ time, they will be.

Find out more about Marcus here; you can also view his Timeout series at weekdays at 101, 1st floor West Wing, Somerset House in London until June.

WIRED.COM by Alyssa Coppleman (20/01/2015)

Photographer Marcus Lyon’s images of crammed megacities and never-ending highways might make you feel like going off the grid. In his claustrophobic series BRICs, Exodus, and Timeout, Lyon creates large-scale visions of globalization and human activity. The images aren’t just photos of Moscow or Mumbai or Marina del Rey, but composites of hundreds of images meant to overwhelm you with the enormity of it all. Lyon’s photographs are minutely planned to the last detail, sometimes years before they are made. After conceptualizing the image in his head—which requires tremendous research and strategizing—he flies over a specific location just once, photographing the ground below. Lyon then digitally stitches together as many as 1,000 photographs to achieve an image that drowns the viewer in congested chaos. The intricate compositions are an artful commentary on humanity’s never-ending expansion and consumption, and the vast chasm between the rich and poor. “Emotionally and environmentally these mass ideas, actions, movements of people, production processes, and the titans of political and consumer power that house them, are so huge that no single image can define their influence,” Lyon says of the work. “So I have endeavored to create new visual languages within which I can communicate a deeper truth.” From Los Angeles to Hong Kong, each photo teems with urbanization. In Lyon’s dystopian vision of the world, there is nary a tree to be seen, and the world is overrun with planes, trains and automobiles swarming across the globe. Lyon weaves his images together so seamlessly that the megacities and mass transit systems he fashions almost could be mistaken for the real thing. Though the work is fiction, the images are familiar, even intriguing, enough to create what feels like a vision of a future that is in some ways already upon us. Considering last week’s news that we’re on the precipice of causing the mass extinction of ocean life, Lyon’s work as a whole serves as a visual prompt to consider more seriously the havoc humankind is wreaking on this planet.

Images from Exodus and Timeout are on view at Somerset House in London through June 1st.

LYON VIDEO on LENS CULTURE by Jim Casper (17/01/2015)

Marcus Lyon has been pursuing his interest in globalization for decades, using both words and pictures to express his vision of the surrounding world. His investigations have taken him across the globe and led him to explore the phenomenon of development through a wide-range of subjects: the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China), the mass migrations of the 21st century and, most recently, the ways in which we spend our leisure time today. Lyon is a visionary photographer who is filled with great ideas and the drive to turn these ideas into reality. We hope you draw some inspiration from the video interview above and the wide range of works he has created during his career, many of which can be found right here, on LensCulture.

LANDMARK in New York Times (07/12/2014)

Vast in its range is William A. Ewing’s LANDMARK: The Fields of Landscape Photography (Thames & Hudson), which covers the world and then some: Among its hundreds of photographs are pictures taken of and from outer space. But variety — topical, procedural, attitudinal — is the point. Nothing in the universe is alien to landscape photography, the book argues, from Philippe Chancel’s view of the construction of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which looks like a cover illustration from a 1950s science-fiction pulp, to Elger Esser’s hazy scene on the Sacramento River, which looks like a sepia-tone 19th-century panorama of the Nile. The subject, however, is the present, and the present is mostly alarming. Marcus Lyon’s depiction of Cape Flats, South Africa, is a perpendicular aerial view, bisected by a highway, with the left half apparently untouched woods and river and the right half a township whose houses are jammed together so tightly their roofs look like stones in a wall. There are pictures of war, of war re-enactments, of psychedelic-looking heavy-metal tailings, of ecological collapse. There are fictional landscapes made with Photoshop, and there are landscapes that look fictional but aren’t — Walter Niedermayr’s vast scene of many evenly spaced skiers on a single slope is, against all appearances, neither movie magic nor a diorama populated by miniatures. The book delivers a pair of oddly coupled messages: The planet is in deep trouble, and its trauma makes for eye candy.